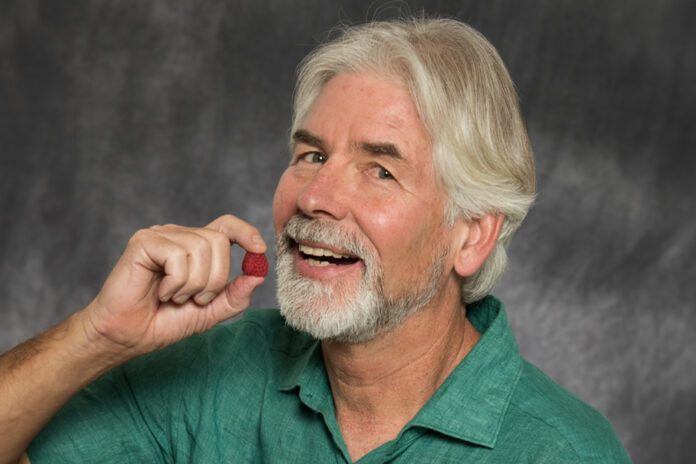

For years, Christopher Gardner, PhD, director of nutrition studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center and a professor of medicine at Stanford University—and a member of the Wellness Letter editorial board—has conducted rigorous randomized controlled trials focused on diet and nutrition. He has authored or co-authored more than 100 academic publications. Despite his prominence in the field, however, his name was unknown to the larger public—until January, that is, when Netflix released You Are What You Eat: A Twin Experiment, a four-hour documentary series. Suddenly, Gardner seemed to be everywhere in the multiverse.

You Are What You Eat was directed by Louis Psihoyos, a photographer and filmmaker whose Oscar-winning 2009 documentary, The Cove, exposed dolphin-killing practices in Japan. The show follows a study conducted by Gardner and his team involving 22 sets of identical twins. One twin in each pair was assigned for eight weeks to a healthy vegan diet, and the other to a healthy omnivorous diet; the filmmakers tracked four of the pairs. They also interviewed other authorities on diet (molecular biologist, nutritionist, and public health advocate Marion Nestle and vegan chef and activist Miyoko Schinner) and politicians concerned about nutrition (New York City Mayor Eric Adams, New Jersey Senator Cory Booker). The study findings themselves were published this past November in JAMA Network Open.

The Wellness Letter recently spoke with Gardner about the experience of conducting a clinical trial while simultaneously being filmed for a TV series, among other topics.

Wellness Letter: How did the documentary series and study come about?

Christopher Gardner: We got a call from the Stanford development office saying there’s some guy there who has money to fund a study that he wants to include in a documentary. So we met the guy [director Psihoyos], and he said, “I have pitched to Netflix the idea of a documentary that would follow a study of identical twins on vegan diets. But I don’t do studies. I don’t know what you would compare it to. I don’t know how long it would be. I don’t know how many people you need. I don’t know what the outcomes would be. What do you think?”

I said this sounded like great fun, and that we should compare the vegan to an omnivorous diet, and it should be a healthy omnivorous diet, not a crappy diet or just telling people to eat their regular diet. There are a lot of studies where somebody had a favorite diet in mind and they compared it to a bad diet. And their diet won—big surprise! It isn’t hard to do better than a crappy one. I said that, to be impressive, we would have to compare the vegan diet to a healthy non-vegan diet. And by the way, I explained, that would minimize our chances of seeing a difference. So I alerted them that they had to be prepared that there might be no difference.

WL: Can you explain why it was beneficial to study identical twins?

CG: The bulk of my research is randomized human nutrition intervention trials. I’ve done around 25 of those. So we had no qualms that we could recruit people, retain them, get them to eat differently, and assess that. When we randomize, we’re trying to balance out the many kinds of differences among people—demographic differences, exercise differences, weight differences. But even when we randomize, there’s still a substantial amount of variability between the two groups that get assigned to different diets.

Given that, the identical twin approach was scientifically intriguing and really just a fun idea methodologically. It was like, wow, being an identical twin will control for more things than we normally do. First of all, they’ll share the same genetic makeup, of course. But it’s also that they were all raised the same way, they had the same backgrounds, they occupied similar socioeconomic positions. These are all factors that can influence outcomes, but they get canceled out when you’re studying twins.

WL: What was it like to conduct a study in conjunction with it being filmed? Did you know much about what the film would actually be?

CG: No, we didn’t. They ended up filming hundreds of hours of footage related to the study, and most of that is on the editing room floor. We knew that they were going to travel around and include other topics and talk to other people, so we didn’t know how much the study would actually be featured. We just knew it would be included—not that it would be the thread of the entire series. So that was something of a surprise.

When they came in to film some of the participants getting blood drawn and so on, they needed Stanford University’s consent. The Stanford media people were cautious and wanted to be assured that this was a legitimate study. I assured them that the study we designed would be publishable—that this wasn’t just something for a TV show. And I had promised that we would get this study accepted in a journal before the Netflix series ran. But of course I couldn’t actually guarantee that, given the vagaries of publishing. I was BS-ing about that. But it worked! The study was published in JAMA Network Open a month before the show appeared on Netflix.

WL: Can you explain what the basic findings were, as reported in the paper?

CG: In the JAMA paper, we covered the cardiometabolic outcomes. LDL [low-density lipoprotein, or “bad”] cholesterol was the primary outcome, and we had a bunch of secondary outcomes. The main finding was that the mean LDL cholesterol of the twins on the vegan diet was 14 points lower than the mean LDL cholesterol of the twins on the omnivorous diet—that’s a reduction of more than 10 percent. Their fasting insulin went down by 30 percent, compared to the twins on the omnivorous diet—that’s also a pretty good drop. And they lost weight.

There were no benefits in cognitive function, but we didn’t expect that. With healthy people, what you’re looking for is a delay in the progression of cognitive decline. But generally healthy people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s, like our participants, don’t have significant cognitive decline, and certainly not over the course of eight weeks. So that wasn’t a surprise. But that was something the producer wanted to include.

WL: The TV series went into some detail about the adverse environmental impacts of omnivorous diets. Your study didn’t address this, but do you agree that eating fewer animal products is better for the planet?

CG: It’s well established that reducing meat and dairy consumption, particularly beef, would have a positive impact on efforts to mitigate climate change, across a range of planetary boundaries—greenhouse gases, land use, water use, eutrophication (nitrogen and phosphorous runoff from fertilization), and biodiversity (for example, cutting down rainforests either for cattle to graze or to grow feed for livestock). Shifting to a more plant-based diet, as was done in this study, would contribute beneficially here.

WL: So what’s your final assessment of the project?

CG: Overall, I feel rock solid about our study and our published findings. I was a little upset that the TV series included information about the subjects’ amount of body fat and muscle, as well as some outcomes related to women’s sexual health. It came across as if those findings were part of the formal study when actually they were not. Those outcomes were only measured in the small subset of participants the film crew was following.

But having said that, I have published hundreds of papers, I’ve gone to many medical conferences, I am the chair of the American Heart Association’s nutrition committee, and yet nothing in my career seems to have had the impact that this Netflix series did. I have been barraged with emails from around the world. I’ve been invited on dozens of podcasts. I was late for a meeting because my neighbor stopped me to say, “Christopher, we saw the show, we’re cutting back on meat, we switched to soy milk.” To hear that is intoxicating! So I’m going to give the filmmaker credit. It wasn’t just an informative documentary—he created something that entertained people as well.

WL: What is the bottom line for you from the study? Should everyone adopt a vegan diet?

CG: No, that was never the intended message. Even before the Netflix series was released, the study was covered in lots of news outlets. And reporters were calling me and saying, “So does this mean you’re recommending everybody go vegan?” I said, “No, I’m hoping people eat more plants and less meat.” Americans eat obscene amounts of meat, they get way more protein than they need, they don’t come close to getting enough fiber. To convince people to change their diets to completely avoid all animal foods is unrealistic. I’m mostly interested in promoting shifts in a healthier direction.

Eight weeks, like we had for our study, isn’t long enough to show significant health differences unless you at least try to make the two diet groups you are comparing somewhat extreme. But you don’t have to interpret the results as meaning that having an extreme diet change is the only way to do it. If you can make a smaller or intermediate adjustment, you would likely get an intermediate result. And it’s important to remember that this was a healthy vegan diet versus a healthy omnivorous diet. I know a lot of vegans who eat horribly—sugar is vegan, soda is vegan, lots of candy is vegan. Just because you have a vegan diet doesn’t mean you eat healthfully.

And Americans are very clever about finding all the ways to have an unhealthy vegan diet, or an unhealthy Mediterranean diet, for that matter. I would really like the take-home message to be that whichever diet you pick, you should pick the best foods in that category. In this one study, in generally healthy identical twins, the ones on the vegan diet did better on some markers. Being on a vegan diet is probably not feasible for many people. So the findings are not widely generalizable, and I’m not expecting the world to go vegan. But I’m thrilled to learn how many people seem to be cutting back on meat and dairy and eating more plant foods because of the series.